This is nobody’s favourite Honda CB750. You only have to look at the prices of good clean F1s. At the same time, there’s quite a strong core of interest for F2s, and these are definitely worth a look. Right now, they’re cheap, but they have a historical significance in that they were the last of the SOHC Honda CB750s as well as being the most powerful.

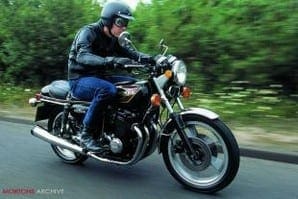

If you think Honda CB750, you think of the classic four-piper. The trouble was that, by the mid-1970s, the CB750 was looking a bit dated. Honda had produced the classic 400 Four, had revamped the CB550 along the same lines with cleaner sportier styling and a four-into-one exhaust, and turned its attention to the CB750.

Year by year the CB750 had shed a little bit of power, and top speed was down as much as 10mph on the 1969 original’s top whack of 120mph-plus. Attention to carbs, breathing, cam etc restored the F1’s power output to a claimed 67bhp – exactly the same as the original’s.

Another major visual change was the exhaust. In came a new four-into-one system, with the header pipes cutting sharply across the front of the block (no delicious curves, as per the 400, unfortunately) and feeding into a cigar-shaped silencer that flared out and then narrowed at the end.

The gearbox was slightly revised as well, with different layshaft and internals. Don’t let anyone tell you the F1 engine was identical to the previous K motor: the bits might have been interchangeable, but there were a lot of minor mods made within those cases.

The bulbous, humbug-like tank was ditched in favour of a slim, slab-sided item, complemented by a nicely-integrated seat and a small plastic tailpiece (Honda giving a clear nod towards Kawasaki’s trademark here). Closer-fitting side panels also slimmed down the looks.

The bulbous, humbug-like tank was ditched in favour of a slim, slab-sided item, complemented by a nicely-integrated seat and a small plastic tailpiece (Honda giving a clear nod towards Kawasaki’s trademark here). Closer-fitting side panels also slimmed down the looks.

The frame was tweaked. The castor angle was reduced and half-an-inch added to the wheelbase, and revised damping improved the front forks and rear shocks.

With the slightly pokier engine and mods to improve the handling, Honda deemed it necessary to uprate the brakes as well and so a second disc was added. At last. Except that, for some reason, Honda didn’t go the route of doubling up the single front disc, despite the fact that the lug for the extra calliper had been on the right-hand fork leg since time immemorial, and every racer and serious road rider doubled the discs as a matter of course.

No, Honda decided to replace the rear drum brake with a disc, and for some extraordinary reason decided to make it bigger than the front rotor, and equipped with a proper opposed-piston calliper. Why they made the back brake more powerful than the front can only be wondered at – my guess is that it was to appeal to the US market, which was used to stamping on old Harley brake pedals.

First reports were quite favourable. The F1 looked good, no doubt about it, and top speed was between 115-120mph so, yes, it was pretty much back to 1969 levels. The suspension mods made a slight difference but, for the rest, it was one step forwards and then a soft shoe shuffle back.

Honda had lopped one tooth off the gearbox sprocket to gear the bike down for acceleration (another hint that the US market was uppermost in their minds) and the thing would spin straight to the 8,500 rpm redline in top. This not only made it feel a bit frenzied, but also meant it drank fuel: 35mpg, if you were lucky. Fortunately, a gearbox sprocket from a K model went straight on, made cruising more relaxed, and rewarded you with at least another 5mpg.

The weird gearing was responsible for another problem: the chain, with the extra load from the smaller gearbox sprocket, needed adjustment every 500 miles when new, and wore out completely by 5,000 miles. Again, a K gearbox sprocket helped its life but still, the silly little chain should have been replaced with a decent O-ring affair.

Oh, and the smart new fuel tank held about three gallons full to bone-dry and so, with the stock gearing, you were running on fumes at 100 miles.

Then there was the frame. Honda CB750s were never great handlers, but the new steering angle seemed to endow the CB750F1 with a straight-line weave that was truly scary. I remember Alan Blake, then a senior man with Avon Tyres, telling me that they tore their hair out trying to get the F1 to behave. They dubbed the sudden weave the “Honda Wander” and discovered you really had to have a ribbed front tyre on it to get it to track straight. Woe betide you if you were running the thing on old, worn TT100s. And if, as I once discovered, you had a rack fitted with a heavy load on it… God, I still blanch at the memory.

Even in 1974 Bike mused that, rather than Super Sports, it was really a fast tourer. The comfort was certainly impressive – decent seat and reasonable riding position, allied with much flatter bars than the four-pipers.

Two bikes conspired to kill the F1 early: the Kawasaki Z650 and the Suzuki GS750, both of which ripped it to pieces in both handling and speed departments. Both bikes appeared in late 1976, and Honda was caught on the hop. With a couple of years to go before its own DOHC bikes were ready, Honda frantically gave the F1 a major revision and called it the F2.

This was what should have been done in 1974. OK, so Comstar wheels weren’t around then, but besides these the F2 got double front discs, much improved suspension, bigger valves, higher compression and accelerator pump carbs to lift peak power to a claimed 75bhp. It was the most powerful SOHC CB750 ever – shame the extra weight rather cancelled out the extra power.

This was what should have been done in 1974. OK, so Comstar wheels weren’t around then, but besides these the F2 got double front discs, much improved suspension, bigger valves, higher compression and accelerator pump carbs to lift peak power to a claimed 75bhp. It was the most powerful SOHC CB750 ever – shame the extra weight rather cancelled out the extra power.

Use of paint cunningly disguised the bits of the CB750 that were old. Matt black paint made the engine look rather racey, and not simply the same old lump that Honda had peddled for the last eight years. Now colours and graphics successfully disguised the fact that the tank and side panels were exactly the same as the old F1’s. Nevertheless, this was suddenly quite a desirable bike, by 1974 standards. Except that it was now 1977. And the GS750 and Z650 were simply better, faster, more modern, better-handling bikes. The only reason for buying a CB750F2 was if you had Honda tattooed on your forehead, or your nearest Kawasaki and Suzuki dealer was 100 miles away.

What goes wrong and what to look for

Not much, mechanically speaking. The CB750 is a strong engine. The extra power made the F2 slightly prone to burning valves if the valve clearances weren’t properly maintained, but that’s about it. On the F1, the horrible old Honda swinging front brake calliper seizes if the pivot isn’t kept greased. More seriously, the feeble chain can snap on the F1, as it did on the Ks, and can take the crankcases out around the gearbox sprocket. Infrequent oil changes can nadger the top end, and as with lots of old Hondas, the small oilways mean that any bodgery with gasket goo is to be regarded with suspicion – it blocks them easily.

If you’ve never heard an old Honda four chuntering at tickover, you may be alarmed – but they all make a lot of noise, most of which is clutch rattle that can be ironed out by balancing the carbs. Check that the 12mm head on the oil filter on the front of the block isn’t rounded off. A 17mm aftermarket bolt is a good investment.

That’s about it, apart from the usual provisos regarding old wiring looms and chrome front mudguards. At least the rear guard is plastic.

For both of them, expect some parts hassles. Some trim is even harder to find than it is for the four-pipers, simply because they didn’t sell many F1s and F2s. ![]()