Take a look at one of Japan’s first, purpose-built, metric chop/cruisers: the Yamaha XV Virago family was mighty popular in its time, and the XV1100 Virago was the daddy of them all and people loved ’em.

Words: Steve Cooper Pics: Gary Chapman

Someone wrote to editor Bertie a fair while ago and asked when we were going to throw some aged limbs across Japanese factory custom bikes – so in response, here we are.

At the time of this photo shoot, it’s the height of the British summer (Bertie doesn’t allow riding people’s pride and joys in winter) and yet (as you might reasonably expect) Mother Nature has thrown all four seasons into one day.

It may be hot right now but there are some heavy clouds amassing, which isn’t necessarily the weather of choice for riding a machine that’s going to take a lot of cleaning if it gets dirty. Fortunately, owner Ron doesn’t seem too concerned and Gary ‘the Lens’ Chapman is delighted with the moody backdrop afforded by the potentially mardy sky. In fact, if you closed one eye and put a patch on the other, our static shots could almost be in America’s midwest where big cruisers come into their own. However, we’re in Norfolk so let’s get down to business.

A walk around the bike confirms the XV1100 is very much a ground-up design and not some hastily reheated dish or a repurposed roadster. What we have here is a prima facie example of a Japanese metric cruiser whose sole purpose was to take sales away from Harley-Davidson in the key American market. The two cylinders are in line with the frame further reinforcing the H-D analogy. That top-end does seem to be vaguely familiar – and then the penny drops… there’s more than a hint of XT/ SR500 about it. I wonder if there are any familial inks here?

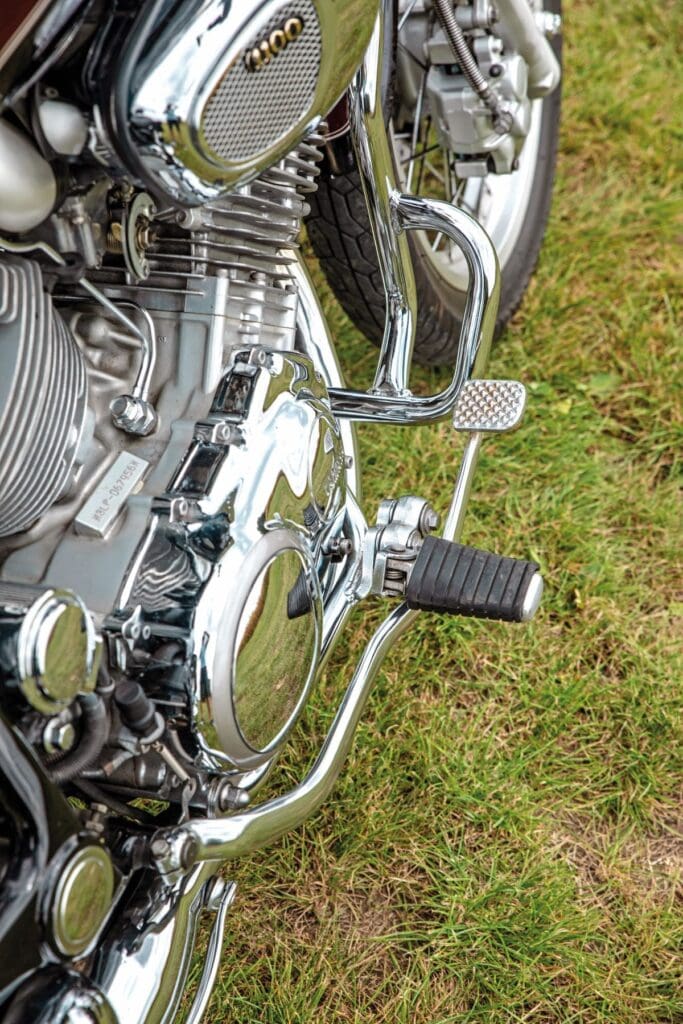

It wouldn’t have been too difficult for XV’s designers to have blinged up the bike to the nines but the styling guys back at Iwata opted not to go OTT. Yes, there’s a lot of chrome to the bike but it’s not excessive so no dazzling mudguards or faux tank panels, just deep, lustrous maroon paintwork. Okay, so there’s shiny stuff on the power unit you’d not have on a roadster but again, in my eye at least, it’s not unwarranted. Initially the wheels look a little odd until you realise that they’re built arse-about-face. The spokes have their angled heads through a special flange on the rim with their threaded endsinside protrusions on the hubs that run at 90 degrees from them; and when you look a little deeper the nipples have hex-heads in their tops. All a little odd perhaps but there must be a good reason for this set up which I’m guessing has to do with the use of tubeless tyres.

As you might reasonably expect, the rider’s eye view is a little different from the norm with a purpose-made dash that features an early generation LCD display advising which gear has been selected (a common add-on in the 1990s). The white-faced gauges bring a touch of restrained glamour to the cockpit without looking gauche. Out towards the ends of those obligatory cow-horn handlebars are two sets of switch gear that are light years away from Yamaha’s 1970s offerings, yet still retain both logical functionality and ease of access; to use that hackneyed phrase …all controls fell readily to hand.

Which also includes the choke actuator so no scrabbling around the lower reaches of the tank for some silly little lever that’s never quite where you think it should be.

The big XV fires up at the touch of the button and, once warm, settles into a reassuring rhythm. It really doesn’t matter where a V-twin comes from – there really is nothing like the feel and sound of a pair of angled pots. Both when static and at speed the exhaust note is muted – obviously Yamaha were ensuring the bike met the then current noise regulations and yet they still managed to engineer some soul into the machine.

In contrast to the short muffler the headers are happy to emit something of a bark. Perhaps it was intended for the rider to hear the living, breathing, soul of the motor but not the public in general? Regardless of the reasons why, the bike definitely isn’t totally sanitised, thankfully. The XV needs some revs to pull away from rest which, again, differentiates it from the Milwaukee offerings. The H-Ds tend to have big, heavy flywheels that aid initial drive but also exacerbate vibrations as the revs build – simply put, you can’t have it both ways.

Out on the road the V-twin doesn’t feel one iota like its American inspiration; the motor is pretty much vibration-free and relatively flexible. Okay, so it may not have the supposed zero-revs-gutwrenching torque of a Milwaukee motor but it doesn’t have the Yank motor’s foibles and vibes either. So far unmentioned, but yet another key selling point of the Yamaha, is the shaft-drive which is totally unobtrusive and never, during our road test, made its presence felt. A chain would have been an easier and cheaper option and, yes, power is lost via the bevel boxes at both ends of the shaft, but it really doesn’t matter on a cruiser at all surely? And this begs the question as to why contemporary Beemers were so sensitive to badlytimed downward changes? Possibly it’s the latter’s engine speed clutch but regardless, the XV never has its rear tyre hopping.

Obligatory on a proper cruiser are the forward foot-rests and King & Queen seat. Even if the foot controls look like they’ll be difficult to operate the reality is the opposite – they become instinctive in minutes. Many K&Q seats are literally a royal pain in the backside, but not this one. The front of the rear perch seems to stop the back of the rider’s seat from being squashed too much and, for me at least, the ergonomics of the Virago proved to be surprisingly comfortable.

There’s an expectation or belief that factory custom bikes don’t handle – the XV1100 is very happy to contradict both assumptions… within the constraints of its design, of course. The big twin handles much better than you might expect and I’d go so far as to say it’s genuinely an easy machine to ride once you realise we’re not talking race-rep steering geometries.

Much of its easy-going nature is probably due to where the bulk of the weight is located. This would appear to be low down so there’s no tendency to suddenly drop into bends because of a high C of G. Ground clearance may be compromised by the low-slung motor and pegs but that’s all part of the metric cruiser image. The frame utilises the engine as a partially stressed member and on the left there’s a chromed rail that weaves its way around the front of the sump and then on to the front edge of the opposite side; presumably this is to dial in some additional stiffness. And, doubtless, the engine protection bars further reinforce the chassis.

Comfort on pretty much any motorcycle depends upon both its ergonomics and the rider’s physiology which is one reason why two people can come away from the same machine with utterly disparate opinions. For me the Virago seemed to suit these old bones rather well. Unlike some more radical custom machines I really didn’t feel my weight was focussed on my tail bone and because of this I genuinely reckon I could pilot the big V-twin long distances.

Now factor in the aftermarket screen taking a fair amount of the wind off the rider and it makes the bike and an even more attractive package – provided factory cruisers are ‘your thing’, of course.

I’ve gone on record before in CMM stating that regardless of popular opinion if the aesthetics of a bike don’t work for me, I generally struggle to bond with said machine. In the case of the XV1100 I’ll happily admit that my self-confessed arty-farty predilections were, initially, neutral at best.

However, once we got a few miles under our collective belt the bike’s easy-going nature rather won me over, but why? Quite simply because it’s unerringly beguiling and I can genuinely see the appeal here.

The bike is easy to ride and doesn’t ask the pilot to make any concessions for its so-called foibles and the like. If character equates to limb-numbing vibrations, apologies for brakes, or compromised ergonomics, I’ll gladly pass thank you. Some might argue our test machine is little more than a heavily sanitised cruiser. I’d strongly counter that the XV1100 is just another example of refined Japanese engineering and one I’d be more than happy to repeat the experience on again.

The Yahama V-twin family

The XV series first broke cover in 1981 in the guise of the XV750H which was supposed to supplant the XS650, parallel twin based Special – it failed by the way.

Scaling the motor up delivered both another Virago cruiser known as the XV920RH and a more traditionally styled ‘roadster’ badged as the TR1. The latter was supposed to be a modern take on the iconic Vincent theme but sales never matched Yamaha’s expectations.

Despite this the firm persevered with the V-twin theme, developing a middleweight sports tourer – the liquid-cooled XZ550. Sophisticated with twin cams and four valve heads, the initial launch model was plagued with issues, leading to Yamaha carrying out a big overhaul. The resultant ‘Mk.2’ proved popular in the US, but not in Europe.

The latter 1980s saw XVs offered as 250, 500 and 535 models with a 700 version sold in the USA to get around the import tariff laws of the time. For years, the XV535 was a popular machine in the UK and Europe, offering the perfect blend of poke and easy-going nature that made it popular with both sexes and those who were somewhat vertically challenged.

A decade later saw the launch of the XVS range featuring 650 and 1100 models. Into the later 1990s the V-twin concept was taken even further with 1600, 1700 and 1900 models sold, all in the cruiser mould. Occasionally Yamaha have revised the V-street bike concept.

The 1100 motor was used to deliver the BT1100 Bulldog which failed to make much of an impression, and latterly the SCR950 street scrambler which did a little better in terms of sales. Further iterations of the V-twin theme have seen the mighty 1700 Road Warrior and VX1900 that was sold under the Yamaha ‘Star’ banner, both of which were again hugely potent metric cruisers. Perhaps the most overlooked of the big V-twins is the machine that launched the MT series – the mighty MT-01.

Very much a concept bike that actually made it to the streets almost unaltered, the bike was for a while Yamaha’s flagship. With a 1700 motor in a unique alloy frame, inverted front forks, R1 brakes and much more, the MT-01 was certainly something rather special.

The owner’s view by Ron Steiger

I bought the XV1100 as a late 60th birthday present to myself. Turning 60, I had a 1980 Honda CB900 that I had owned for six years. My wife wasn’t too keen on the Honda as the seat height was quite high and it took a huge effort by her to get on it.

Having slipped while attempting to get on and falling backwards she dislocated her left wrist, fracturing it in three places. Obviously after several weeks in a plaster cast plus weeks of physiotherapy, she was not in any hurry to get back on the bike.

So, we went window shopping for something with easier access. Having spotted the 1996 Yamaha XV1100 Virago I was impressed at how smart it looked and we both said yes! Sitting on the Virago, she was in heaven. She could get on and off without even having to step on the left rear foot-peg and hoik herself up on it. Because the seat height was so low, she literally just stepped over the bike seat and settled on it. When I first got on it, I had a hard time finding the foot-pegs as this was the first time I’d ridden a bike with forward foot controls. After a couple of attempts with my feet looking for phantom pegs it all came together.

I’ve never known a first gear so fast on a cruiser; most people refer to them as a crawling gear but not in this case. Then change up until you’re in top, and you’re at a decent speed. If you want to overtake or go uphill, there’s no need to change down, just open the throttle and off she goes! And there’s a lovely, thunder sound coming from the engine. The only downside is cornering. With a 19-inch front wheel and a 15-inch rear wheel, and a long wheelbase, it doesn’t lend itself to being the scratcher or suited to knee-down cornering. But what it does do is glide around bends and after slowing you can negotiate tighter bends. I wouldn’t trade it for anything, I love the ride and the looks it gets when I park it up – worth every penny.

Specification

ENGINE TYPE

1063cc, air-cooled, four-stroke, V-twin, SOHC

BORE AND STROKE

95 x 75mm

CLAIMED HORSEPOWER

61.7bhp @ 6000rpm

MAXIMUM TORQUE

58ft/lb @ 6000rpm

TRANSMISSION TYPE

5 speed

COMPRESSION RATIO

8.3:1

CARBURETION

2 x BST40 Mikuni

TYRES

110/90 x 19 (F) 140/90 x 15 (R)

FUEL CAPACITY

3.7 gallons (16.8 litres)

BRAKES

2 x 2282mm disc (F), SLS drum (R)

WET WEIGHT

241kg (531lb)